|

| Powerful me, circa 2001 |

To be fair, I could have landed at the bottom of that hole and lay in the gravel, whimpering quietly. I could have ignored the bits of rope that were dropped down to me. But scratch the ripped version of me climbing triumphantly to a mountain top, shall we? Try this image instead: A whimpering me lay at the bottom of a hole and cautiously called out--not wanting to disturb anyone. Then the ropes that came down somehow magically wrapped themselves around me and my friends with their powerful friend muscles did the work. Yes, I asked for help, but I must give credit where credit is due--they pulled me up.

I read an article yesterday about raising children with invisible challenges or disabilities like ADHD or autism. It said that it's helpful for parents to compare invisible challenges with physical disabilities to help people understand. Here's her example:

Yes! That idea does make me cringe. We'd never think a child in a wheelchair just wasn't trying hard enough to use her legs. That analogy got me thinking about the invisibility of grief which makes it difficult to describe and difficult to understand. Over the last 18 months since Riley died, I have tried to come up with a useful physical analogy to describe my parent grief. My latest is that losing him is like losing my arms. Think about it. Think about what your life--or even just getting through a day--would be like if your arms were amputated. No fingers, no elbows, nothing. And while it is difficult to imagine things we haven't experienced, like that article, I suspect that imagining our bodies minus limbs is somehow easier than imagining our lives minus our living children.

Given that I’ve had arms all of my 42 years, life without them would never get easier. I would still be able to walk and move around, but every single thing would always be hard. I’m sure I’d figure out how to eat and brush my teeth, use the computer and the toilet (but not at the same time), but I would never be okay with losing my arms no matter how many years went by and how many beautiful people I met at occupational therapy and support groups who also had lost their arms. I would always, always miss having arms.

I read an article yesterday about raising children with invisible challenges or disabilities like ADHD or autism. It said that it's helpful for parents to compare invisible challenges with physical disabilities to help people understand. Here's her example:

I am raising two older boys with physical challenges...I have never - ever - had to justify a single accommodation that they required. Can you imagine a school official saying...."well, you know if your son just tried a little harder, he could get out of that wheelchair and run up the stairs and then we wouldn't need to build a ramp." Are you cringing yet?

|

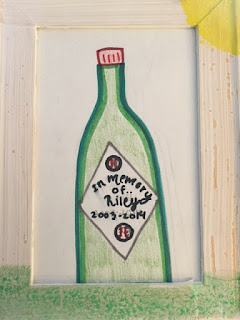

| Sibling grief art |

Grief is invisible, and it’s hard to understand or empathize with if you aren't enduring it. So this analogy is my (latest) effort to help the non-grieving world (and the not-yet-grieving world because life is a series of losses, is it not?), what losing Riley is like. I will never be okay with losing him and every single thing will always be hard. Always. Because, like amputation, death is permanent. I would always, always miss having arms. I will always, always miss my son. Even if I'm trying to get out and do things that I did before Riley died, I will never be "better." I will only be different.